In 1870 the Indianapolis Asylum for Friendless Colored Children opened at Mississippi and 12 th Streets (eventually re-named Senate Avenue and 21 st Street, respectively). Unsettled by homeless, impoverished, and often-ill African-American newcomers, Indianapolis’ Friends (Quakers) resolved in 1869 to organize an African-American orphanage (compare the histories by Thomas Cowger and John Ramsbottom as well as the Indiana Historical Society collection guide). The families were compelled to contend with Hoosier racism and segregation in their new home, and they were among the many newcomers whose lives were transformed by impoverishment and a segregated social service system.Ī migration wave in the wake of the Civil War first exposed Indianapolis’ lack of institutional support for the newly freed African Americans who escaped north. James Edmonds and his three children came to Indianapolis in 1890, and Price and Amy Lessenberry and their four children followed in 1898. Fueled by post-Emancipation optimism as well as a sober acknowledgment of Jim Crow racism, many African-American families went north to cities like Indianapolis. The two Kentucky families were part of a wave of African Americans who swelled the Circle City’s population in the early 20th century.

In the 1890s the Lessenberry and Edmonds families were among the scores of African Americans migrating to Indianapolis.

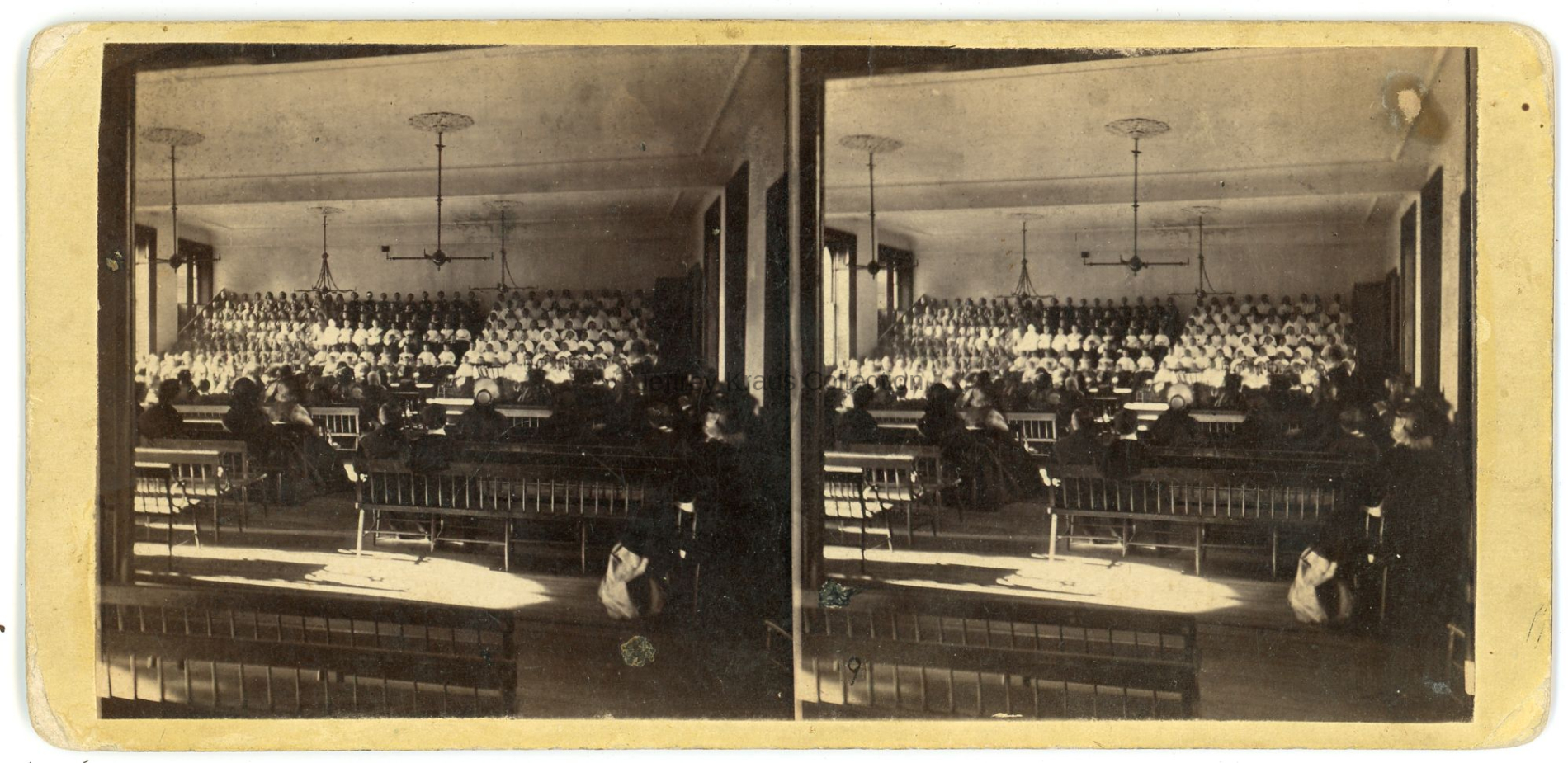

A recent merger with Children’s Village in Dobbs Ferry has expanded its reach in providing family services.In July, 1892 the Indianapolis News provided this imaginative picture of children at the Colored Orphan’s Home (click for an expanded view). After a series of mergers, the COA survives today in the Harlem Dowling-West Side Center for Children and Family Services. It was also at this time that the trustees started to work with Harlem churches to strengthen their mission of providing for orphaned, neglected and delinquentĭespite its shortcomings, the orphanage providing nurturing, education, lessons in morality and stablity to children who otherwise would have been left on the streets. The first African American trustee was not brought in until 1939 and shortly thereafter the first Jewish trustee. With the exceptions of James McCune Smith who served as physician for twenty years, and a few teachers or matrons, the colored staff was limited to menial positions.

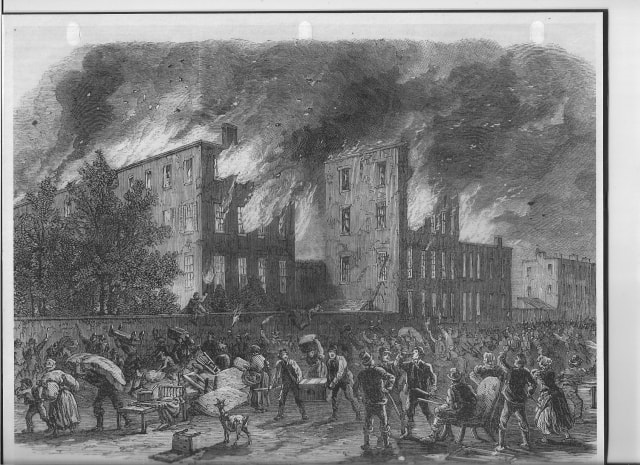

The Riverdale site is today the Hebrew Home for the Aged.īy the time it closed in 1946, the COA had provided care for approximately 15,000 children, yet its trustees/managers were reluctant to treat African Americans as equal partners. It remained there until 1946, when the COA shifted from a residential institution to an emphasis in foster care and adoption. After the Civil War a new COA was built in 1868 at 143rd Street and Amsterdam Avenue.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)